(The initial post this information relates to is here.)

Some interesting questions have been posed regarding Okafor Theory and the underlying data. Some responses are below.

Why do you hate Jahlil Okafor?

I don’t hate Jahlil Okafor. I wrote these things about him:

Okafor has a more polished and impressive offensive post game than any college freshman, perhaps in history.

big men are known to take a while to learn how to play good defense, and Okafor is only 19 years old. He could very well become a great defender in a few years

In many respects, he is indeed a great offensive player.

suction cup hands

Are you really stupid enough to believe Duke would be better without Okafor this season?

Nope, not that stupid. Duke has 8 eligible scholarship players, and 2 of them are centers. Without Okafor, Duke would have 1 center on its roster this season, who happens to be somewhat foul-prone, and would go at most 7-deep. That’s rough. Without Okafor, Duke would’ve struggled mightily this season.

Based on the stats at sports-reference.com, Okafor has absorbed the burden of using 28% of Duke’s possessions when on the court this season, while putting up a very nice 122 offensive rating. He has a fantastic 32 PER. He’s extremely valuable to Duke and, appropriately, he’s currently 7th on Kenpom.com’s national player of the year rankings, which is entirely objective and stats-based. He’s a near lock to be 1st Team All-America and might win a few national player of the year awards. He’ll probably be the #1 pick in the NBA draft. He deserves all of it.

However, Duke may be even better as a team if, say, his usage decreases from 28% to “only” about 24%, and an extra 3 possessions per game go from being Okafor post up attempts (or turnovers) to being spot up 3s for Duke’s many great 3pt shooters or Tyus Jones trying to get to the line with his outstanding 55% free throw rate and 87% free throw percentage. 24% usage would still be a lot. Someone who uses 24% or more of a team’s possessions is often considered the star player on that team. As a hypothetical added bonus, carrying less of the burden on offense might be beneficial for Okafor’s defense, though this is merely speculation.

Okafor’s team has the #1 adjusted offensive efficiency in the country and you’re concerned about offense?

Sure, because even #1 can possibly get better. Okafor’s team having the #1 offense is a testament to his offensive skill. He’s asked to do things in the offense that would be extremely inefficient for the vast majority of basketball players on any level, let alone a freshman in college, and he makes it work to a great extent because he’s a transcendent talent. I’m interested in whether there are realistic ways for his team to improve by tweaking how they use him.

Okafor didn’t even play against Clemson, and Clemson is terrible. Doesn’t that data skew the results?

The Clemson data is more data. It’s pretty much in line with all the other data and provides a larger sample size of possessions. In fact, eliminating the Clemson data would make the Okafor-on-the-court efficiency margin look even worse relative to the Okafor-off-the-court margin for ACC games.

Clemson, arguably, is not terrible. Duke without Okafor made Clemson look terrible, yes. Clemson is currently the #86 team on Kenpom.com. Duke has played 4 out of its 15 ACC games against teams worse than Clemson in efficiency.

There is no reason to believe the Okafor-on-the-court numbers against Clemson would have been better than the Okafor-off-the-court numbers if Okafor had been healthy and played. All of the other data suggests this likely would not be the case. Removing the data for Clemson doesn’t affect the broader analysis at all.

What cherry picking and sorcery did you use in these so-called “advanced stats” to make your point?

There was no cherry picking. The ACC games provide, in my opinion, the best neatly describable pool of data, because the ACC provides very good competition relative to non-conference schedules, and the ACC games are the latest games to look at. Recency and decent competition are good.

Looking at games when Rasheed Sulaimon (dismissed from the team) and Semi Ojeleye (transferred from the team) were getting minutes for Duke, for example, doesn’t seem nearly as helpful as looking at games in which Duke is using players it will actually have for the rest of the season. Looking at Duke’s 69-point victory over Presbyterian to begin the season, in which there were several possessions involving walk-ons and players who no longer cared about what they were doing, likewise seems less valuable (the Presbyterian data actually increases the gap between the Okafor-on-the-court results and the Okafor-off-the-court results).

There is nothing “advanced” in the analysis. The spreadsheet with the data has two arithmetic functions in it: 1) divide one cell by another cell; and 2) subtract one cell from another cell. Ken Pomeroy’s basic explanation of possessions and efficiency may be helpful. Any idiot could have run through the play-by-play of each game to get this data. I am the idiot who chose to do so.

Why is per possession efficiency information any more useful than something like plus/minus per 40 minutes?

If someone were to look into Duke’s plus/minus stats per minute (or per 40 minutes) with Okafor on the court and with Okafor off the court, those stats would tell the same general story as the per possession stats. Regardless, per possession stats seem to be more useful for a few important reasons, and one reason is highlighted by this very case.

Okafor has played noticeably more possessions on offense than on defense this season. This is not because Okafor is somehow generating extra possessions for his team when he’s on the court; that’s not how possessions work. Okafor often comes out of games starting with defensive possessions and often enters games starting with offensive possessions, and this occurs most frequently in offense/defense substitutions at the end of halves. What this leads to is Duke with Okafor playing more possessions on offense than on defense and Duke without Okafor playing more possessions on defense than on offense. To control for this, we can look at possessions rather than minutes. Again, even with the skew in favor of Duke with Okafor on the court when looking at plus/minus per minute, the numbers will generally tell the same story.

For example, in the game against Virginia Tech, Okafor was subbed in and out for offense/defense quite a bit. The non-Okafors ended up playing 9 possessions on offense and 17 possessions on defense. If they had scored 9 points on those 9 offensive possessions and allowed 17 points on those 17 defensive possessions, they would have looked bad based on plus/minus per minute (minus-8 over however many minutes), but why would anyone care about a per minute number in that case? The team would be exactly even per possession, at 1 point per possession scored and 1 point per possession allowed, with an efficiency margin of zero. That seems like a much more useful way to measure how well a team performed, given that a team can only score while on offense.

What about all the other considerations, like the players Okafor is up against and the players the non-Okafors are up against, the teammates Okafor has with him on the court during any given possession, how much the players care about certain possessions as compared with other possessions throughout a game, the effect of an opponent game planning for Okafor and not so much for the non-Okafors, etc.?

That sounds interesting. Someone should gather that data and analyze it.

One consideration that has easily accessible data pertaining to it is intentional foul possessions (i.e., when Okafor is off the court at the end of a game and one of Duke’s excellent free throw shooters is fouled intentionally to be put on the line, doesn’t this skew the results against Okafor on the court?). I looked into this. In the aggregate, these possessions do not change the analysis. There were also possessions when Okafor was on the court while Duke was shooting intentional foul free throws.

Isn’t the sample size too small to draw any conclusions from?

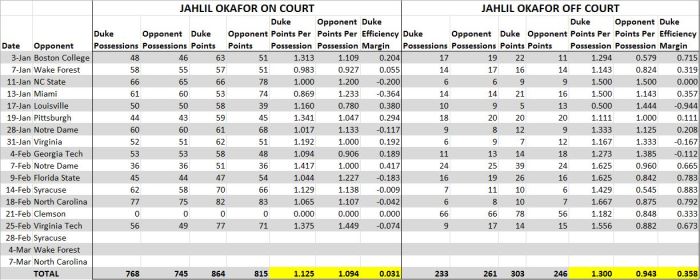

If you believe 233 Duke possessions without Okafor and 261 opponent possessions without Okafor in ACC play are, in fact, not large enough samples to draw meaningful conclusions from, that’s fine, but it should be much more difficult to believe that 768 Duke possessions with Okafor and 745 opponent possessions with Okafor in ACC play are not large enough samples to care about.

If we completely ignore Duke’s phenomenal ACC efficiency margin with Okafor off the court because we don’t believe 233-261 data points are sufficient, and if all we look at is Duke’s meager ACC efficiency margin with Okafor on the court, then there are still some startling results. Duke has outscored ACC opponents by only 0.031 ppp with Okafor on the court.

John Gasaway analyzes in-conference efficiency margins throughout the college basketball season in his Tuesday Truths column. Based on his most recent data, a 0.031 ppp efficiency margin would place Duke 6th in ACC play this season, behind NC State and ahead of Miami. Duke with Okafor on the court has performed like the 6th best team in the ACC.

More sample size?

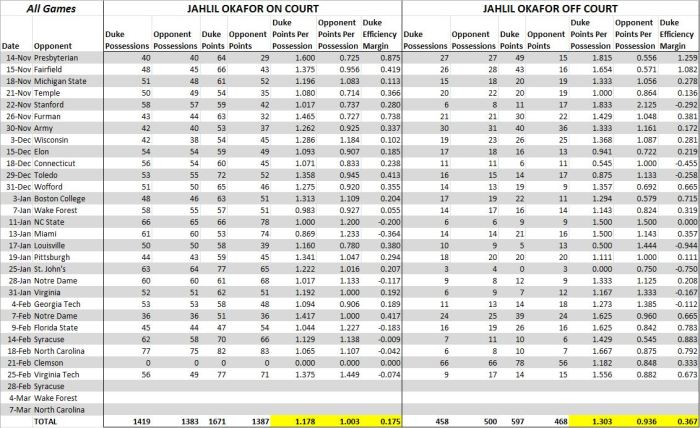

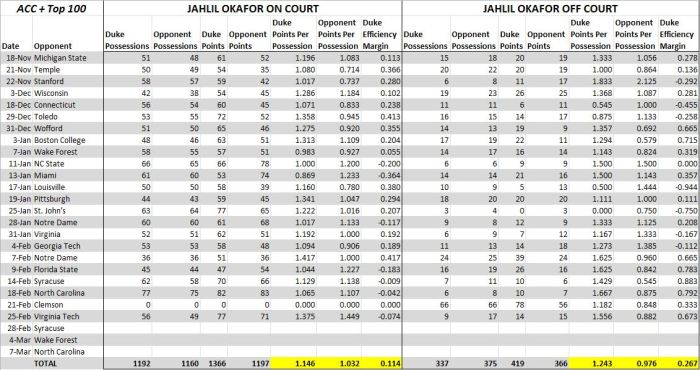

Below are the full season results, as well as results including all ACC opponents plus non-ACC opponents that are currently ranked in the top 100 on Kenpom.com (click to enlarge).

The full season results are in line with the ACC-only results discussed in the initial post. Duke with Okafor on the court looks a little bit better with all games included, rather than just including ACC games, but is still significantly worse than Duke with Okafor off the court, both on offense and defense.

One reason I chose ACC + Top 100 as a pool of games to look at is because the full season results are skewed by a disproportionate amount of Okafor-off-the-court possessions against truly terrible opponents (not merely Clemson-terrible). The non-Okafors performed much better than the team with Okafor against Presbyterian and Fairfield to start the season, for example, and there were a disproportionate number of possessions by the non-Okafors in those games.

In the ACC + Top 100 pool, the gap between Duke’s performance with Okafor on the court and Duke’s performance with Okafor off the court is at its narrowest. However, Duke with Okafor off the court has still performed significantly better than Duke with Okafor on the court, both on offense and defense.